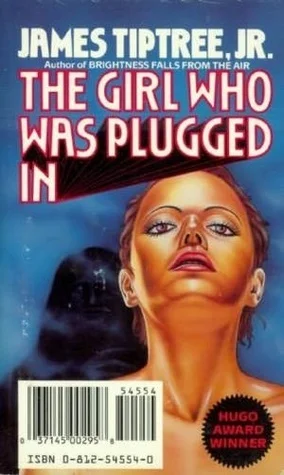

The Girl Who Was Plugged In Is Must Read Proto-Cyberpunk

“It’s a lucky girl who can have all the fun she wants while doing good for others, isn’t it?”

Published in 1973, James Tiptree Jr may not have created cyberpunk, but pretty much wrote cyberpunk. The only major thing missing is the injection of The New Frontier trope. Full on cyberspace found in Neuromancer isn’t present. When people discuss proto-cyberpunk fiction this short fiction piece should be a major component, especially when looking for non-masculine works within the-subgenre that don’t get put on must read lists as much as they ought to (I’m working on mine presently, by the way).

In just 36 pages, it tells the story of 17-year-old P. Burke in the near future who makes a suicide attempt that is denied by a bureaucracy. Instead, she is offered a job presented as the opportunity of a lifetime. She is to be a remote, broadcasting her consciousness into a 15-year-old clone with receivers built into it, but otherwise completely devoid of sentience. This body is crafted into the ideal image for the consumers who will be watching her on a feed. The job? Simply live her life, entertaining the consumers glued to their feeds, what are explicitly drawn to her as a desirable commodity, even though we know as the reader her job is essentially Sex Sells. Her actual objective is to use selected products she’s supposed to like so that others may see them and buy them. After all, they are the best products if she likes them.

“And here is our girl, looking—

If possible, worse than before. (You thought this was Cinderella transistorized?)”

It’s capitalism as we know it with one major difference: there’s no ads. They’ve been banned. Kind of. The neon tinged fever dream-like streets we’ve come to associate with cyberpunk focuses on the way in which people living in capitalism become consumers in unsuspecting ways. Although there are no ads exactly, this only means companies have adapted, creating new ways of getting people to buy. Most predominantly: product placement. I imagine this might just be starting as a thing in 1973, but I couldn’t speak intelligently on that. Turns out it was a reasonable anxiety to have back then; go figure.

These new gods of society, as they are called often, are fickle; moving from new fad to new fad so quickly that companies cannot cash in well enough. And so they need their own god, controlled by them.

The Girl Who Was Plugged In is both explicit and stark in its condemnation of the ways in which society dictates every acceptable action a woman may take to accrue some modicum of power. Even when Delphi—the persona which was created for the real live P Burke, described as being an ugly woman and is kept in a basement somewhere—accrues said power, temporarily becoming indispensable because she is a taste maker—her power is only a loan, and as fleeting as the masses interest; never truly accrued and earned and kept like the puppeteers behind the scenes truly benefiting from societal structures. And it also has very real limits, as we find out.

“Don’t worry about a thing. You’ll have people behind you whose job it is to select the most worthy products for you to use. Your job is just to do as they say. They’ll show you what outfits to wear at parties, what suncars and viewers to buy, and so on. That’s all you have to do.”

When she meets a young man who falls in love with her, his desire is linked to her body only. Even though he is the son of the man who owns the company and described as essentially woke and awake of the ways in which the system preys upon the weak. He does not know that a remote exists. He never actually sees the woman behind Delphi, even though everything beyond her presentation is present as well. He doesn’t want to know her mind. His rage is tied to his ability to own his notion of what a free Delphi is, never asking her what she wants or needs. The comfortable feeling that what he wants to consume is in front of him parallels the damage well-meaning allies, that are actually just a part of the same system of control, visit on people tied up in systemic oppression is disturbingly articulate.

A biting critique throughout, and a through line for non-masculine cyberpunk works, it’s a formative piece of literature for the sub-genre. One that does not feature some of the more problematic aspects first wave cyberpunk often is critiqued for.

“Every noon beside the yacht’s hydrofoils darling Delphi clips along in the blue sea they’ve warned her not to drink. And every night around the shoulder of the world an ill-shaped thing in a dark burrow beasts its way across the sterile pool.”

While the world is brutal to the protagonist, like pretty much all cyberpunk, the marginalization of and fetishization of P. Burke, as she is referred to in the text, is the entire point of the story, serving to critique societal structures. Even with this critique present, there is also no feeling of the male gaze perforating the short fiction. It some ways it is as large a contrast between some of the more typical first wave cyberpunk and the non-masculine works found in the sub-genre. Certainly nothing could surpass it in this condensed a demonstration of the contrast, anyway.

It becomes even more unsettling in its presentation, which feels very much as though you’re a viewer of a program yourself, being taken for a ride that is exciting and supposed to be acceptable. Watching P. Burke’s rise and fall written like a program written you’re going to enjoy when you ought to feel sick.

“…showbiz has something TV and Hollywood never had—automated inbuilt viewer feedback. Samples, ratings, critics, polls? Forget it. With that carrier field you can get real-time response-sensor readouts from every receiver in the world, served up at your console. That started as a thingie to give the public more influence on content.

Yes.

Try it, man. You’re at the console. Slice to the sex-age-educ-econ-ethno-cetera audience of your choice and start. You can’t miss. Where the feedback warms up, give ‘em more of that. Warm—warmer—hot! You’ve hit it—the secret itch under those hides, the dream in those hearts. You don’t need to know its name. With your hand controlling all input and your eye reading all the response, you can make them a god…and somebody’ll do the same for you.”

You can find The Girl Who Was Plugged In in a collection of James Tiptree Jr’s short story collections called Her Smoke Rose Up Forever.