The Relationship Between Posthuman Fashion And Humanity Cost in Cyberpunk 2020

“If my nightmare is a culture inhabited by posthumans who regard their bodies as fashion accessories rather than the ground of being, my dream is a version of the posthuman that embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality, that recognizes and celebrates finitude as a condition of human being, and that understands human life is embedded in a material world of great complexity, one on which we depend for our continued survival.” - N Katherine Hayles

in March of this year at BreakoutCon 2018 my friend Hamish Cameron, author and designer of The Sprawl RPG, asked me if I'd read Cyberpunk and Visual Culture; in particular, an essay in it titled "'Today's Cyborg Is Stylish': The Humanity Cost of Posthuman Fashion in Cyberpunk 2020". I hadn't at the time but months later while designing Veil 2020, my minimalist retro cyberpunk RPG for The Gauntlet gaming community's monthly zine, Codex; I did.

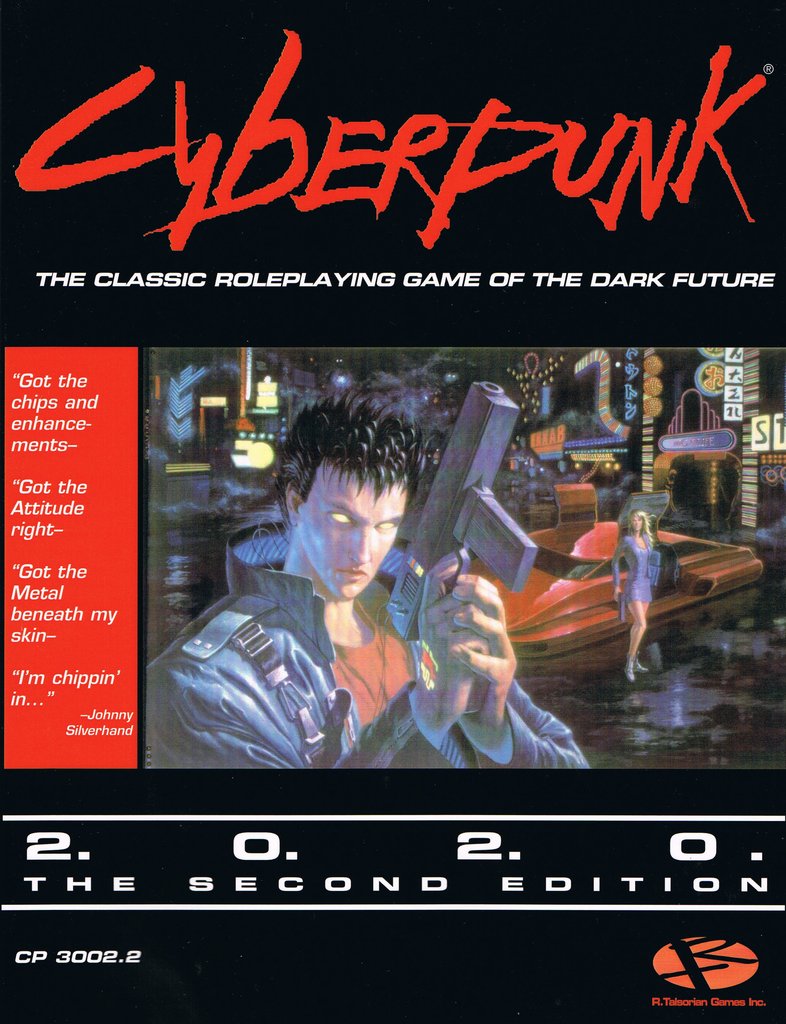

Cyberpunk 2020 has an excellent authorial voice (Mike Pondsmith). From the very start of reading it, the first thing you see is somewhat typical of 90's tabletop games, a sexualized woman in lingerie except she's also got a cyber arm, setting the stage, so to speak, for what's to come. Also attempting to appeal to the demographic of folks buying games at that time, no doubt.

From the Cyberpunk 2020 corebook

The next thing you read is that you're going to be playing a cyberpunk in a "violent, dangerous place, filled with people who'd love to rip your arm off and eat it...you do what you have to do to survive. If you can do some good along the way, great." You find a cause your cyberpunk can get behind and throw yourself at it. To be a 'punk you need to internalize three concepts. The most of important of which? Style over substance.

As you read on the authorial voice continues to reiterate that your entree to this subculture is through fashion and through augmentations via various cybernetics. From chips that go into your head to bolster you to the chromed arms on display previously—your subculture is defined by style. How you do a thing and what you look like doing it matters.

"In Cyberpunk, what you look like is who you are. Fashion is action and style is everything"

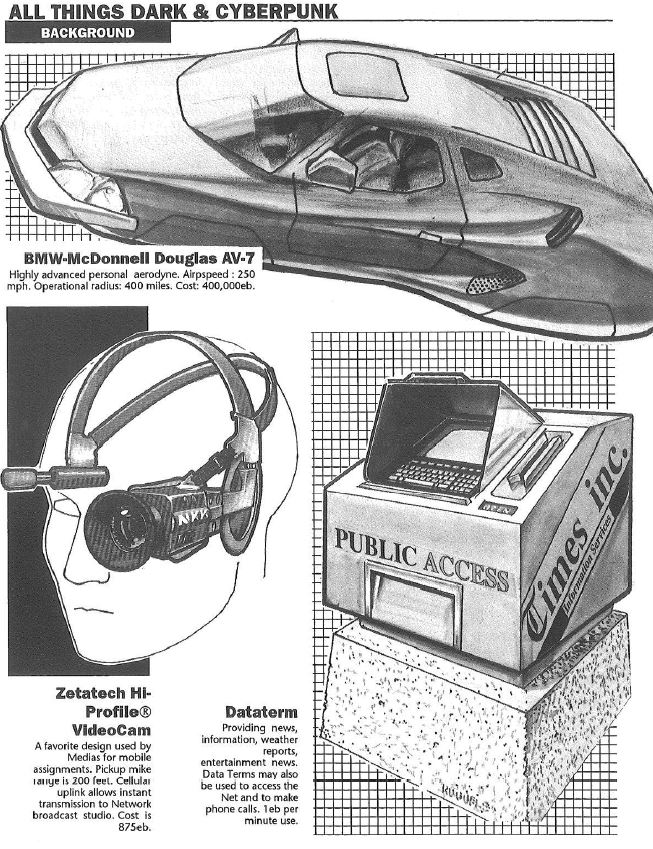

Stina Attebery and Josh Pearson argue in their essay that by putting this central to gameplay, players are encouraged to incorporate psychological and technological vulnerabilities into their characters in order to pursue this aesthetic the corebook works hard to build in every facet of the reader's consumption of the material; from art to the layout, to the authorial voice. This, I think, is without question for me. The game presents cyberware and guns and the like as though they were a catalog, literally "selling" you these items and depicting them as desirable. In later supplements, the upgrades emulate the look of consumer brochures.

From the Cyberpunk 2020 corebook

Beyond this, though, they also posit that by anchoring advancement and development of the character "in fashionable expression shows that posthuman fashion, as a self-conscious style project that is central to the genre of cyberpunk, can destabilize subject/object relationships and invite risky new ethical identities for human subjectivity embodiment." I would also add that by having players on a meta level function as consumers for their characters they are are also adding to this dichotomy.

Because tabletop games are collaborative, players are active participants in the hypocrisy of the game. You're purchasing things as a consumer all the time in order to fulfill your goal of expressing yourself, ostensibly while doing harm to the systems and structures placed there that would only seem to perpetuate our capitalistic reality. This game, unlike some others, is not overly concerned with this at first glance. As Mike Pondsmith, the author of the CP2020 corebook said, "cyberpunk isn't about saving humanity, it's about saving yourself." The text and images presented make it easier for the players to generate a character that is an expression of an identity different than their own. It's "cool" to look different; be different; act different, and to fuck up people who would hurt you and hate you because you are different. In fact, a lot of adventures feature factions and groups that are primarily concerned with hurting people who identify as cyberpunk. Namely: you.

From the Cyberpunk 2020 corebook

So then. You want to embody someone with cyberware and fashion in this game. It is "what the game is about." It is positing that by forging an identity of an "other'd" person, you are in fact resisting; even if you're also interacting with commodities and products, your self-expression is by appropriating these commodities and products into subversive elements that are the primary focus of your fiction. The "style" of play.

"The perverse, unnatural use of clothes can articulate new gender definitions and destabilize apparently fixed notions of reality and materiality from the nation to individual subjectivity. Commodities, in other words, can be deployed against the cultural, libidinal, economic, and identitarian logic that they also appear to support." -- Maurizia Boscagli

As a player, you're shopping a catalog of subversive elements and then using them to craft an identity. In essence, using the skills we have as consumers in order to "game" our characters cyberpunk identity. Potentially a transformative experience, or at least a unique one; especially at the time of publication in 1990.

Then the game puts these decisions front and center in the fiction with Humanity Cost. Along with your "cool" stat in the game, you'll also find your "Empathy" stat, which is a "measure of how well the character relates to other people and is the basis for such skills as leadership, lying, convincing and romantic relationships." In CP2020 "the ability to be 'human' can no longer be taken for granted" because of the setting, in which most of the people are framed as survivors of a dystopia, cyberpunk or otherwise.

Different cyberware and augmentations cost varying amounts of Humanity Points which are calculated from your Empathy stat; 10 points for every point of Empathy. This means the more modifications you get the more your ability to empathize with others is reduced. The less flesh and bone you have, essentially, the more your ability to empathize with everyone else is degraded at a mechanical level. Eventually, you may even get cyberpsychosis, suffering a mental break. It could even get to a point where you lose control of your character and have to give it to the Referee (the person facilitating your game).

From the Cyberpunk 2020 corebook

Mechanically this signals to the player that beyond the aesthetic that is prevalent, these choices are inherently risky. There is a cost beyond money that is associated with the identity you're forging for yourself.

In the essay, they posit that this could be leveraged by a player in the spirit of the game and allow a player to "tell a nuanced story about the connections between augmentation, identity, social relationships, and institutional power." Citing an example of a player doing just that to create a veteran who was heavily cyberized after being hurt badly in action and having only 2 Empathy left after the alterations. The play example was extremely positive.

So even as you're maximizing the potential of your character as a player, there is a dichotomy introduced mechanically into the framework of the game, even more so if you create a social character. You could kit yourself out to be an amazing performer, another example in the essay, but with your decreased Empathy you would be less able to participate in the experience you're creating through your augmentations. Every decision in the game is framed as being risky, right down to your self-expression and identity.

Often times when Humanity Points are in a cyberpunk game it signals to me that, well... it's old and reflective of the 90's fear of technology rather than more nuanced takes 25+ years later. However, I can appreciate the mechanical framework and scaffolding because these mechanics serve a clear purpose. Every tabletop game text is trying to help you recreate a specific experience at the table and the mechanics, I think, serve this purpose.

What cannot be denied, in my opinion, is that is not representative of some marginalized people. While there may well be social and psychological repercussions of having a prosthetic, in this system if you used technology to have your character's sex organs altered, for instance, that would also reflect a loss of humanity. Problematic and not reflective of today, let alone the future when presumably even more technology will be utilized and ubiquitous in the average individuals lives. Having a game system decrease your humanity because it's reflective of your own lived experience before you even get playing is understandably something a lot of people aren't going to be interested in. Since the time of writing, we augment our lives with even more technology and do not think of ourselves as less human, even if it does affect the way we socially interact with others.

This mechanic does reinforce the theme and tone of the game, though. Which is more credit than I had initially given it; initially outright dismissing the mechanic entirely as the technophobia of its time. Of course, people playing in the spirit of the game can create the play experiences written about in the essay, which is great! The Referee and players can always house-rule, altering the Humanity Cost mechanic to conform to items that might play toward what the game is trying to explore. What should cost humanity and what shouldn't, if you're keeping the mechanic in your game. But... if you're inclined to do that, why not play a cyberpunk game that doesn't have Humanity Cost and Points. There are many now, whereas back then, this was seminal work and cyberpunk tabletop options were few and far between.

People often conflate some of the problematic content designed for the game as something produced by Mike Pondsmith and R. Talsorian Games. The content produced directly by the company does have some of the 90's marketing stuff you'd expect but it does not have the problematic aspects some people recall; the adventures people made for the system are the culprits. Hopefully with the direction of Mike Pondsmith directly we can expect something that isn't problematic in Cyberpunk 2077.

We already know Cyberpunk 2077 is going to feature the humanity Cost mechanic. Empathy is back, displayed in the demo for press-only at E3 of this year. Will these mechanics translate well into a video game? Have they been at least updated, presumably along with the setting? With so little known about it still, it's hard to know what this means for the game.